I needed a break. So did Drew Pomeranz.

Out of MLB since 2021, the lefty reliever owns a 0.00 ERA through 16 appearances for the Chicago Cubs. Will the success stick?

Last month, I published a glowing review of Griffin Canning’s performance so far this season. On Wednesday, June 4th, the Baseball Gods (and Canning himself) rewarded my faith with his best outing of the season — seven strikeouts and just three hits allowed over six innings of shutout baseball. The Mets came away with a decisive 6-1 win over the Dodgers, a victory that also secured the regular season series.

As I left Dodger Stadium to start the long trek back to my apartment in Hollywood, I realized how long it had been since I published that piece, and similarly how long I’d left my Bluesky unattended: a whole seven days, an eternity for me.

Simply put, I was burnt out. I needed to take a minute to regroup and get myself back into peak typing form.

You know who else had to take some time to get back into peak form?

Drew Pomeranz’s MLB journey is one you’d write a movie about.

Initially drafted in 2007 by the Rangers and then drafted again in 2010 by the then-Indians, Pomeranz was traded to the Rockies in July 2011 before finally making his MLB debut on September 11, 2011. He would spend three seasons in Colorado bouncing between the bigs and Triple-A before heading to the Athletics, where a change of scenery led to a positive change in results.

After two successful years in Oakland, the A’s traded Pomeranz to the Padres, where he was named an All‑Star in 2016. He was traded again in 2018, this time to the eventual World Series champion Red Sox. After signing with the Giants in free agency in 2019, he struggled as a starter and was traded once again, this time to the Brewers. He transitioned into a high-leverage reliever role in Milwaukee, posting a 2.39 ERA down the stretch and eventually securing a four-year, $34 million deal with the Padres in free agency. Unfortunately, persistent injuries limited him to just 44.1 innings from 2020 to 2021, after which he missed both the 2022 and 2023 seasons due to surgery and setbacks.

Now a member of the Cubs — his seventh MLB franchise — Pomeranz is 36 years old, seemingly healthy and picking up right where he left off.

Is his comeback the real deal? Let’s dive in.

What’s Working?

The Fastball

In my aforementioned piece about Canning, I acknowledged that his fastball was working better for him than it had at any other point in his career. The same can be said for Pomeranz right now.

Canning, however, is not historically a fastball guy. Pomeranz very much is.

Throughout his career, the fastball has been Pomeranz’s bread and butter (his ~40% curveball usage in 2016 notwithstanding). Even when his repertoire featured a sinker, a cutter, and a changeup, his four-seamer has always been his primary pitch. More often than not, it has been deployed as his put-away pitch of choice; it’s either that or the knuckle-curve.

So, why is it such a particularly effective pitch this year?

See that bright red column? Let’s semi-quickly talk about spin rate.

Spin rate is exactly what it sounds like: it’s the speed at which a ball spins out of a pitcher’s hand, measured in revolutions per minute (RPM). Driveline Baseball published a comprehensive breakdown of how spin rate impacts a given pitch’s movement and effectiveness, but for our purposes:

A 92 MPH fastball at 2200 RPM is going to travel on an ‘average’ path to the plate.

If this 92 MPH fastball is thrown at 1800 RPM that means less spin, less Magnus force meaning the ball will drop further over its course to the plate than the ‘average’ fastball described above.

If this 92 MPH fastball is thrown at 2400 RPM that means more spin, more Magnus force meaning the ball will drop less over its course to the plate than the ‘average’ fastball.

These are small enough differences that a batter would not be able to tell before they decide to swing, but the balls will end up at different heights by the time they reach the plate.

—Driveline Baseball, “Spin Rate: What We Know Now” (2016)

To date, Pomeranz’s fastball spin rate (2591 RPM) is one of the best in baseball, ranking in the 98th percentile among active pitchers. Considering he throws his fastball at around 93 MPH, that would mean his fastball has significantly more spin than the average fastball. When paired with an 84 MPH curveball and elite command of the strike zone, that makes it a very deadly tunneling weapon. (More on that later.)

When measuring fastball effectiveness, though, spin rate only tells half the story. We also need to consider something called Bauer Units.

Named after everyone’s favorite former MLB starter Trevor Bauer, Bauer Units (BUs) help to further contextualize how spin rate influences a pitch’s effectiveness relative to the velocity at which it’s thrown. This is especially important when discussing fastball movement:

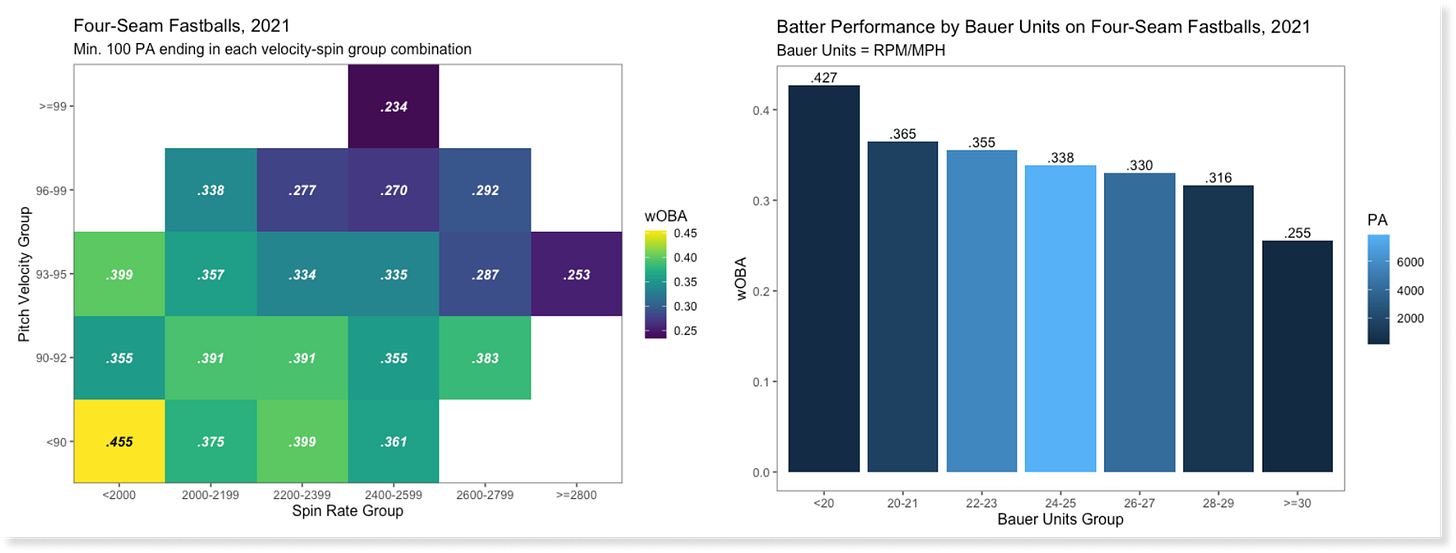

I also looked at batter performance by Bauer Units, which is effectively a velocity-adjusted spin rate. It’s a simple calculation — RPM/MPH — but it does the trick at calculating velocity-independent spin and rewarding pitchers if they have an abnormally-high spin rate on pitches with lower velocity even if those raw spin rates are not as high as those on pitches of higher velocity.

—Devan Fink, “More Spin, More Problems: Hitter Performance Against High-Spin Fastballs.” (2021)

In his 2021 piece for FanGraphs, Devan Fink (now in baseball development for the Orioles) explored why hitters have a harder time against higher-spin fastballs. He found the following:

Of the data sampled, Fink found that hitter wOBA fell off significantly as velocity and spin rate increased. However, since spin rate is influenced by a variety of factors, he also sought to use Bauer Units as a more independent evaluator. The velocity/spin rate trends held steady.

While I don’t have access to the exact league-average numbers from this season, a quick Google gives me the following numbers for 2025:

Fastball velo: ~94 MPH

Fastball spin rate: ~2300 RPM

Using the Bauer Unit calculation of RPM/MPH, we get a BU median of ~24.5 for the 2025 MLB season, which directly matches Fink’s original charts. That would put Pomeranz’s fastball well over 30 BUs, which further explains the .159 wOBA opponents have managed against his heater this year.

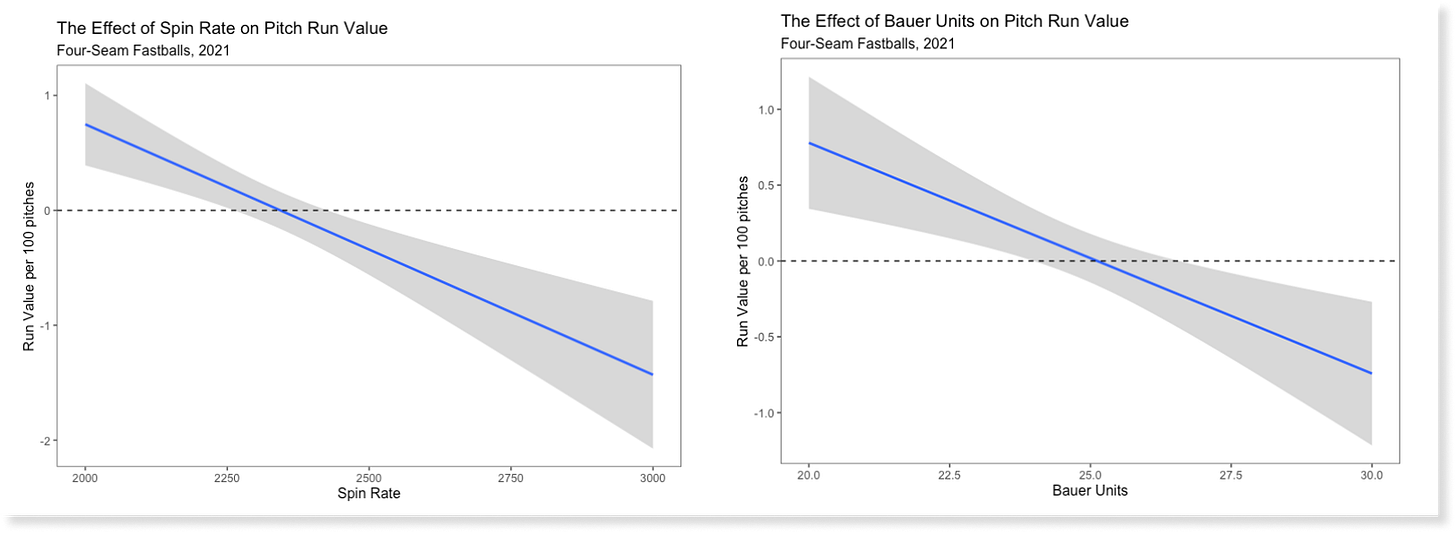

However, Fink wasn’t done: he also sought to measure how spin rate/Bauer Units affect pitcher run value (RV).

Fink found that, “on average, an increase in 100 rpms on the four-seam fastball increased the pitch’s run value by 0.2 runs per 100 pitches. An increase in one Bauer Unit, meanwhile, increased the pitch’s run value by 0.16 runs per 100 pitches.”

If we use the same 2025 league averages as above (94 MPH, 2300 RPM), that above-average spin rate performance would directly attest to Pomeranz’s fastball’s current +8 RV rating.

And believe it or not, all of the above is just the tip of the iceberg.

Pitch Sequencing & Placement

Throughout his career, Pomeranz has never been one to dominate hitters with overwhelming velocity, instead relying on a lethal fastball-curveball combo that can expand the zone beyond the point of recognition.

Looking at Pomeranz’s 2025 heat maps, here’s what I’m seeing in a nutshell:

Smart pitch placement.

Command of the zone.

Remember earlier when we talked about the Magnus force and how a fastball thrown with a higher spin rate will take longer to drop vertically? When paired with an 84 MPH curveball that can fall anywhere in the zone, that already excellent pitch becomes that much more functional.

When you’re only working with two pitches in your repertoire, sequencing and placement go hand-in-hand. Since you can’t throw hitters off by switching up the pitches you choose to show them, you have to be very smart about what you throw, when you throw it, and where you throw it.

Since Pomeranz is a fastball-heavy pitcher, what he’s able to do is set a tempo with the fastball, get hitters out of rhythm with a curve that’s thrown roughly 10 MPH slower, and then either freeze the batter on strike three or disrupt their timing just enough that they’re not getting to the ball in the ideal timing window.

That strategy seems to be working, as Pomeranz is averaging 3.83 pitches per plate appearance.

(Plus, how else would he be able to pull off this many called third strikes directly over the middle?)

And speaking of strike zone command, Pomeranz should be loudly praised for his significantly improved walk rate this year. It currently sits at a measly 5.7% — compare that to the league average of 8.4%, and his own career average of 11.8%.

By managing to drastically reduce the number of free bases given up while maintaining his career strikeout rate (28.3% in 2025 vs. 27.3% career), Pomeranz has come out of the gates looking like a retooled, reinvented version of his very best self, rounding out an excellent Cubs bullpen that currently ranks 4th in the NL in ERA (3.39).

But…is he just lucky?

…Maybe. At least a little bit.

I take no pleasure in suggesting that Pomeranz’s resurgence is entirely lucky, trust me. I don’t even really believe it to be true — it’s too simple an explanation.

But, as encouraging as his performance has been, I also have to acknowledge both portraits being painted by the available data: one of a finesse pitcher who hasn’t lost a step despite years of setbacks, and the other of a pitcher who has benefited greatly from a variety of convenient circumstances.

Expected Stats

Not only is Pomeranz giving up the second-highest average exit velocity (EV) of his career, but batters are hitting the ball at an ideal launch angle (LA) nearly 41% of the time they put the ball in play. He’s also surrendering a nearly-20% barrel rate, by far the worst of his career.

While his xBA of .227 doesn’t scare me much, here are the numbers above that do concern me:

4.32 xERA

4.25 xFIP

.458 xSLG

.337 xwOBA

.426 xwOBACON

43.8% Hard Hit rate

And they don’t get any more reassuring.

Quality of Contact Stats

In addition to a career-high barrel rate, Pomeranz is also pitching to more solid contact than he ever has before.

In general, Pomeranz is giving up the highest solid contact rate of his career; the same goes for his barrel rate. He’s also yielding the lowest ground ball rate of his career: 25% vs. his career average of ~44%.

And the more I look at the batted ball data, the more concerned I get:

Even though it’s a small sample size, it needs to be noted that Pomeranz is giving up a barrel rate that’s three times that of his career average (18.8% vs. career average 6.14%).1 He’s already given up twice as many barrels as he did in his last Major League season on half the sample.

Look a bit deeper, it gets a bit scarier:

Of the 24 field outs generated by Pomeranz this season, 10 of them were hit over 300 feet in the air; of those 10, four were hit both in the LA sweet spot range (between 25°-35°) and at an ideal EV (≥90 MPH). The remainder just barely missed those parameters. All it takes is a change of scenery or environmental circumstances for some of these close calls to turn into runs scored:

I’ll concede that I might be sounding undue alarm bells on this point specifically…but an 18.8% barrel rate and career-high contact rate are two things any pitcher could find themselves on the wrong side of.

(I’m obviously not rooting for that to happen.)

Wrapping Up

Overall, I’m encouraged by what Pomeranz has shown so far in his return to Major League action. His fastball looks electric, and he’s locating it with pinpoint precision. Playing off the movement and sometimes wild placement of his curveball, it’s an elite weapon that can dominate hitters anywhere in the zone, even directly down the middle when it’s set up properly.

However, I think it’s fair to say that I’d like to see more before declaring Pomeranz “officially back.”

The variables coming into play in the quality-of-contact department are eye-catching, and despite looking every bit like the Pomeranz of yesteryear, I wouldn’t be surprised if we saw him endure a rough stretch later this summer as hitters get more looks at his stuff. That 0.00 ERA isn’t going to last forever.

Still, I think Pomeranz will be just fine. I wouldn’t be surprised to see him closing out important late-season games, and maybe even playing a big role on a playoff roster.

Time will tell.

I know this isn’t a perfect comparison, as the sample sizes from 2015-2019 are far larger than those of 2020-21. However, the lack of significant deviation in the numbers from year to year relative to his 2025 mark, despite a significant change in workload and a developing injury history, tells me that this range is generally where he’ll sit regardless of external circumstances.